Another way of saying this is that Lent is a season for reorienting our lives toward joy and beauty. So I think a worthy Lenten practice is to look at whatever spiritual discipline we may have set for ourselves over the course of the Lenten season, or throughout the year, and ask one simple question about it: Is it preparing me to embrace joy?

Another way of saying this is that Lent is a season for reorienting our lives toward joy and beauty. So I think a worthy Lenten practice is to look at whatever spiritual discipline we may have set for ourselves over the course of the Lenten season, or throughout the year, and ask one simple question about it: Is it preparing me to embrace joy? Asking this question might lead us to realize how much we have been missing, but there we find the timeless lesson of the gospel: it is never too late for joy to find its way in. And as the story of Mary anointing Jesus’ feet reminds us, beauty and joy are an incalculably valuable part of what it means to be human.

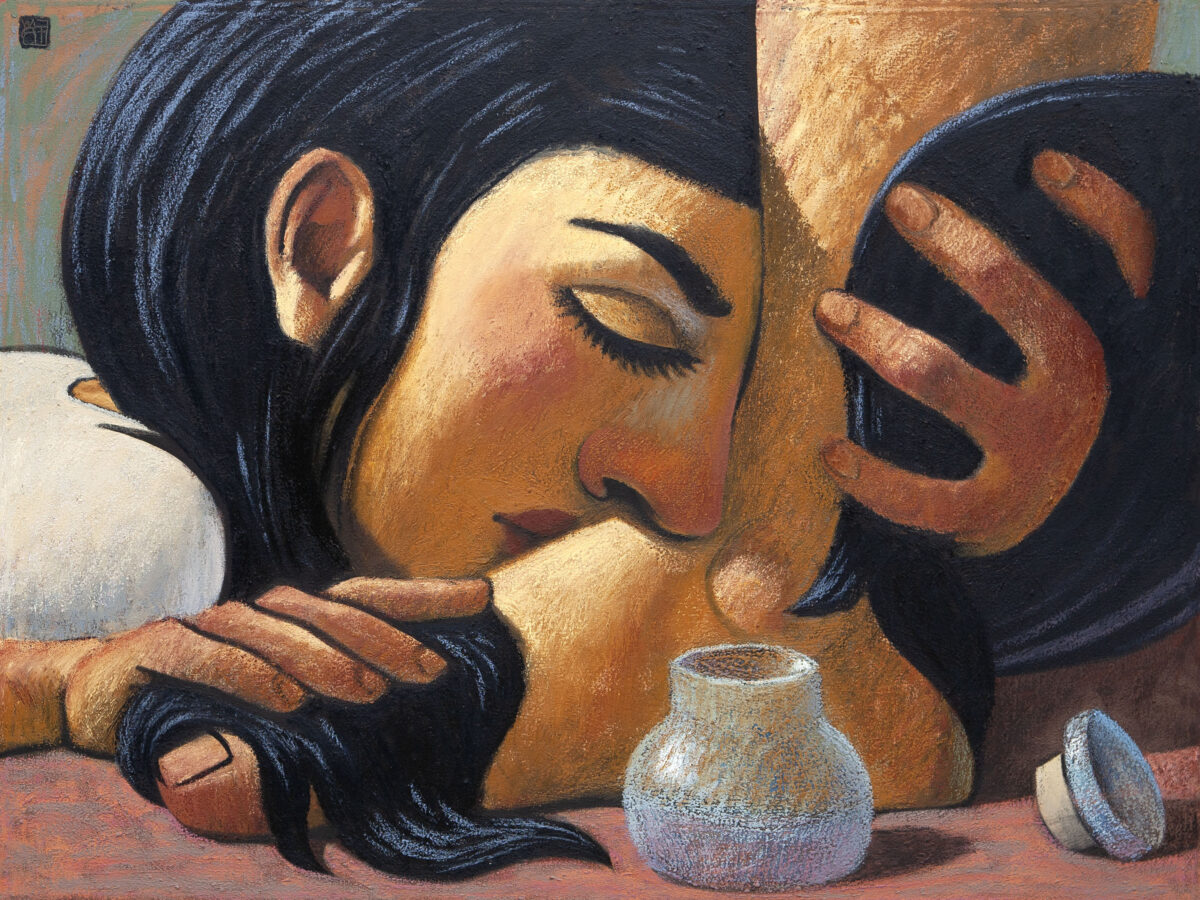

In nearly every artistic representation of Mary anointing Jesus’ feet, it is hard to deny the sense of intimacy created by the scene. In more modern depictions, the focus is primarily on Mary. Only Jesus’ feet are shown, with Mary’s face and hair drawing the viewer’s attention. I think such modern depictions help to place the viewer in the position of those who witnessed the event itself. And from that position, the viewer is challenged with a question: Am I beholding an act of love that is beautiful in its own right, or am I just seeing a scene whose value is only related to the cost of the perfume that was used in creating it? Do we see the scene as the Christ saw it, or do we see the scene as Judas saw it?

All too often, I think, we see things from the perspective of Judas, and his attitude echoes our own: there is so much work to be done, so much need in the world to be addressed, that we should forego beauty and joy because beauty and joy are just superfluous luxuries. Who needs them? When it comes to appreciating and pursuing beauty while also caring about the world’s needs, we are usually met with a particularly tricky temptation. The temptation is to identify something in the world that needs changing and to adopt a sort of tunnel vision in which we set our eyes on the desired change and assume that anything that detracts from it must be wasteful or wrong. The problem with this way of thinking, though, is that even if our goal is actually good, it eventually cuts us off from the possibility of beauty and joy. And while we may be accomplishing a good, practical work, if we sacrifice beauty and joy to accomplish it, then the work itself can become rather dry and lifeless.

For example, if one wanted to address the need for affordable housing for low income families, one could argue that building on a plot of land bordering an industrial zone would cut down on costs. The savings would allow the addition of an extra floor in an apartment block. If providing green space could be left out of the plans, that would allow for more apartments. And if paint could be eliminated from the budget altogether, that would allow for even more apartments. The problem is clear. If all that matters is providing four walls and a roof for as many people as possible, then one might well achieve one’s goal, but the living environment thus created would be tragically joyless.

When it comes to spirituality, I think many of us wrestle with the temptation to think of spirituality in purely transactional terms. To the decidedly skeptical mind, cultivating spirituality is just a waste of time that could be better spent bringing about real change in the world. Even for those who are drawn to things like prayer and meditation, however, there might be an unspoken admission that prayer and meditation don’t have any real power to fix what is broken in the world. So, the argument goes, spirituality really is an extravagant squandering of our time and resources. But this is to misunderstand the power of beauty and the practical role that joy plays in human life.

In one of my favorite stories from the Christian monastic wisdom tradition, a visitor goes to a monastery. The visitor sees the monks going about their daily routine and notes that every couple of hours they make their way to the church to spend time in prayer. The visitor concedes that the architecture is beautiful, the chanting is inspiring, and the atmosphere is peaceful. But the visitor notes that there’s no school, there’s no hospital, there is no observably “practical” ministry. To the visitor, it all seems very self-serving and insular. After a few days, the visitor asks one of the monks, “I see that you pray a great deal, but what do you do?” The monk replies, “We do not do. We are.”

The same sentiment can be applied generally to spiritual practice. Genuine spirituality is not focused on purely practical or transactional outcomes. Like the creation of art, spiritual practice is not so much geared towards a final product upon which a worldly value can be placed. Rather, spirituality is the expression of a longing to connect with the source of joy and beauty. To the skeptic, following a spiritual path might seem to serve no practical purpose, but for those who are drawn to it, the search for beauty represents the height of human endeavor and the true end toward which all practical pursuits aim.

That is why I think it is no mistake that places of worship are often where the arts flourish. If the creation of art flows from a desire to add beauty and joy to the world, or to critique the ways in which the human spirit is stifled, then it makes sense for houses of prayer to be beautifully adorned. Stained glass windows, carvings, paintings, and other such works are not mere extras that add no “real value” to a space. Quite the contrary, they both add to, and are the product of, the pursuit of beauty and joy that is at the heart of all spiritual practice. In that sense, art in a house of worship – and in our daily lives – is very much like that costly jar of ointment that Mary poured on Jesus’ feet: the beautiful result of overflowing love that enriches the world beyond measure.

The Rev. Rob Donahue

Canon Precentor, Grace Church Cathedral

Charleston, South Carolina

May 2022