This text is not acting as a polemic, but in this brief reflection, I pose the question of whether it is possible to add an invested, respected, and motivated platform or appeal for religious complexity in art ecosystems, alongside everything else. From the position of thinking of balance, I would ask what kind of frameworks can be visioned to think about this from the perspective of adding to the ecosystem rather than taking away, outside of the commonplace conceptual black hole of deconstruction. I am going to turn to a framework, not one from art history or the sciences of Western academia that have been the dominant paradigm of contemporary art knowledge production. I am turning, in the spirit of the point of this text, to a framework that my grandparents taught me, that my parents taught me, that I learnt in my daily schooling in an East London madrassa as a child – a framework from the traditional Islamic sciences. A framework of Mizan. To speculate a perfect balance for the scales. In the Holy Qur’an, the primary conceptual thread that permeates its poetics is the concept of the oneness of Allah, the divine and all-knowing, who has cast this world, its actions and its interactions in a logic no human soul can comprehend. The Muslim faith is to believe in this divine order – to give yourself an understanding that there is a balance to everything, even if it strains the soul or doesn’t align with rational perception. One concept often drawn out to refer explicitly to this balance is Al-Mizan. Mentioned in a few contexts in the scripture to mean the scale of divine balance that Allah has prescribed for the world and every soul, but also of how one’s actions and contributions to this world will ultimately be judged when this world ends. The day of Judgement. Youwm Al-Quiyaama (یوم القيامة.). In this scale of judgment, there is infinite mercy and vengeance.

This concept feels instinctively incongruent when thinking of the logic and cultures of the contemporary professional art world. Even typing the previous paragraph for a text which has an intention to be read by various elements of the contemporary art ecosystem (artists, curators, gallerists, art museum administrators, etc.), I can feel my ears going red with judgement. The Day of Judgement? Allah? Scales of divine balance? Speaking of these things as reality, as belief, as per my faith, within many unquestioned cultures of the art ecosystem will instantly bring images of someone who is an outcast from the contemporary art space. Am I a risk to values enshrined in this ecosystem, and even a risk to the presumed critical and cultured fertilizer that allows art and artists to flourish? A risk to freedom? In opening the conversations around religion and belief in contemporary art, I have sometimes been met by the response, ‘this (art gallery/museum/discourse) needs to be a secular space’ – but what does this mean?

There has been a flattening of the complexity of religion and belief, and positioning of its presence as incongruent, despite the embrace of multiplicity: a sleepwalking into a slumber of secularisation in contemporary art frameworks, systems, and institutions. Secularisation, in the academic sense, represents a dominant philosophical and cultural position that flowered in the 1950’s and 60’s, and correlated modernity to mean the retreat of religion. As society advances, the belief, practice, and importance of religion decreases. Secularisation in its brief conceptual mainstay, was quickly readdressed in the light of a reality which in both quantitative and qualitative measurements countered any claim to say religion has a natural place in ‘project modernity’.

It is of significance to note that there has been much in the emerging literature since the 2000s that reopens dialogues on religion, belief, and spirituality within contemporary art in this conceptual domain. Whilst it may not be said explicitly, the principles of secularisation still have a strong presence within the contemporary art world. It is in the DNA of the arts professionals trained in questioning everything and deconstructing the world in the Foucault and Bourdieu or Marx and Deleuze campuses, studying the breaking of traditions in art history with the black squares of abstraction. The white wall galleries across the world, like secular embassies, make modernity transnational, presenting artists as gateways of transcendence, whilst wrapping them in a discourse where deities don’t make the rules.

Yet, there is significant glory in contemporary art’s questioning of structures and authorities for liberatory thinking. Manifesting the experiments of artists who can vision new intellectual, aesthetic, and ethical territories, often pushing forward with various stakes of support to signal progressive virtues outside of the realm of tradition. The progressiveness in recent decades has also pushed forward the readdressing of inclusion around identities on the margins whose presence in the dominions of art history may not have been on the surface. We have seen powerful statements addressing equity through representation in many art museums, whose echo has even penetrated the art market to arguable degrees.

A liberal voice has been fashionably loudest in the art world. Religion in this context is unfashionable as a living and practising belief, and functions as a signifier of a tradition that is anti-progressive. It only can be digested through conversations about cultural identities or post-secular dialectics that merely celebrate the shared commonality of a diversity of beliefs.

Thus, it is not just the unravelling of sacredness that goes alongside secularisation, but also a perception of religion as counter to the well-intentioned progressive identity of art ecosystems. Now, of course, there can be a righteous and contextual anxiety of religious authority being an adversary of art and artists – a mechanism of flattening freewheeling expression and experimentation. Personal and collective experiences have witnessed religion as an oppressive force in its dogma, nationalism, authoritarianism and/or hostility to difference. Islam often functions as the popular phantom placeholder of this in global currents and narratives. These negative associations and experiences all too easily have become tied to how religion is defined, or the emotions it evokes, in the contemporary art white-wall ecosystem.

I speak pithily in this broad observation, but I suspect that I evoke weak confidence at best, and at worst triggered anxiety when religion and belief are brought within the discourses and spaces of contemporary art. Particularly when religion isn’t positioned as a concept, or a context, or an aesthetic, or a history – but as a lived reality of belief. There is nuance in this dialogue that has not yet been fully embraced.

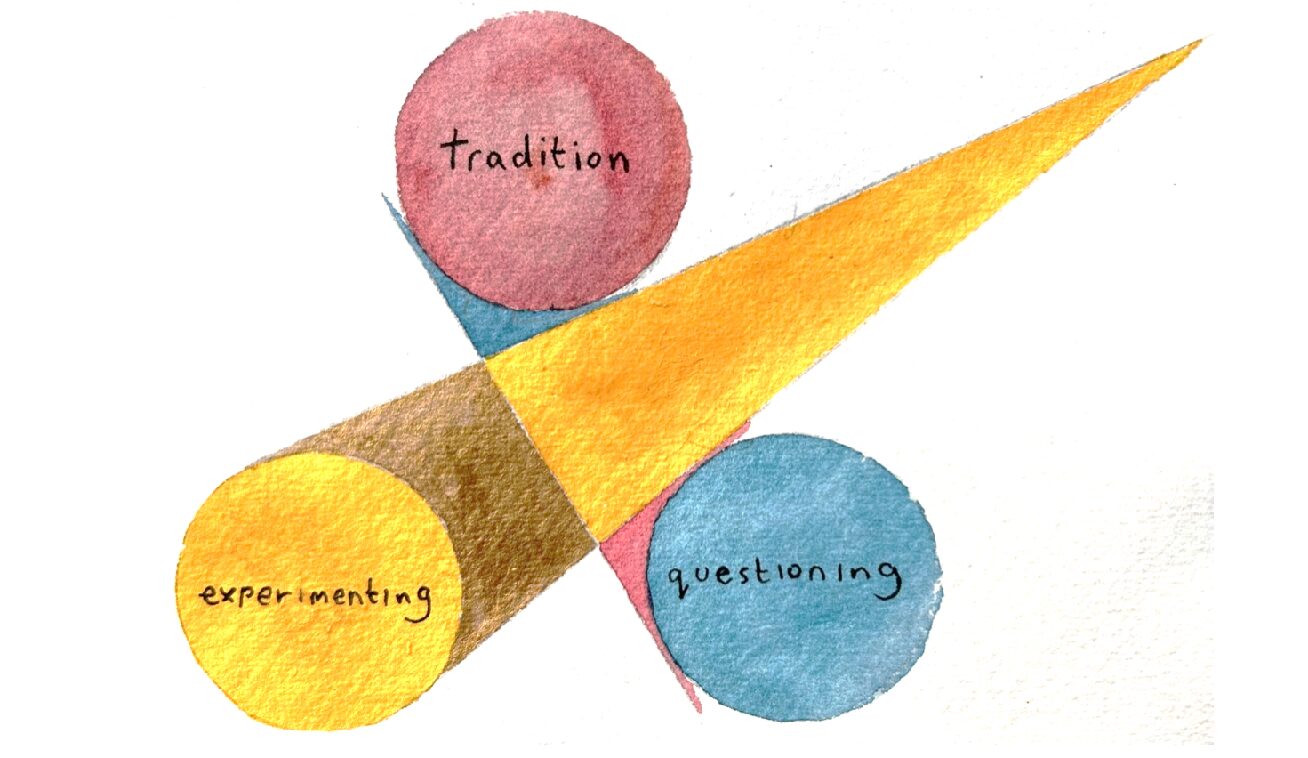

Let’s consider a speculative proposal of balance that I have begun to explore – an artistic Mizan – which nourishes art’s innovation void of nihilism. I see an artistic Mizan to be found in the following equation: 1/3 tradition, 1/3 questioning and 1/3 experimenting. This equation can be translated into institutionalised thinking and individual dispositions for the museums and galleries and the artists and curators, and all the necessary anchors that create value within contemporary art.

There is sahih hadith, an authentic narration from the life of the Prophet Muhammed (peace be upon him), that was canonised in the Sunni tradition by the Persian scholar Ibn Majah (209 AH/824 AD – 273 AH/887 AD), stating that the Prophet once commented: ‘A human being fills no worse vessel than his stomach. It is sufficient for a human being to eat a few mouthfuls to keep his spine straight. But if he must (fill it), then one-third of food, one-third for drink and one-third for air’.

The perfect meal. The evocation of finding the Mizan, the divine scales of balance, in every act. Making every act one of potential devotion. Drawing on this, what can be the elements to create that Mizan for contemporary art? A balance to allow a reconnection in the significance of the divine as a living belief, whilst letting the spirits of artists be in the frontiers of uncharted openness.

If the divine balance in a meal is 1/3 food, 1/3 water and 1/3 air, then to keep the spine straight within contemporary art, maybe we can find the Mizan in a similar formula. In the ecology I outlined, perhaps the mesmerising nature of questioning and experimenting has tipped the scales off-kilter, at least in the fashionable discourses most visible. Flowing freely without direction in the pool of secularisation and neo-colonial progressiveness.

In this speculation, we can value orthodoxy in belief and practice, communities that organise around these beliefs and practices, and the traditions that ground these systems and make room for them to exist in their confidence. This acts as a counterweight to the questioning – where questioning doesn’t simply exist to deconstruct meaning. It can exist to keep the foundations of tradition strong, and with this value, the questions become more meaningful. In this speculation, we can think of possibilities where art institutions dialogue with religious institutions to help articulate traditions, and in turn, where religious institutions develop stronger arms of questioning their purpose, relevance, and structures.

This leaves the final element: experimenting. The visioning of the artist – the freedom to innovate through tradition, experimenting in ways that can express the complexity that diffuses the secular, and the religious beyond binaries. These elements, 1/3 tradition, 1/3 questioning and 1/3 experimenting, all in balance, not only can bring a meaningful complexity of religion and belief into hard relief in the contemporary art ecosystem, but they can also facilitate the most challenging, prophetic, and profound art to be made, pushing the confidence of artistic risk further.

It is of significance to note that there has been much in the emerging literature since the 2000s that reopens dialogues on religion, belief, and spirituality within contemporary art in this conceptual domain. However, here is another gap in the system: much of this emerging narrative doesn’t turn its focus on to the technical mechanics of institutional practice. The mechanics of what informs the professionalism within the art museums and galleries – the policies, guidance, and processes. It is why so often the best and most innovative practices of having dialogues with religion and belief within contemporary art museums happen because of driven individuals with personal motivations – but once they leave or move on, the programme, projects or foregrounding go with them.

So, what can this look like, beyond a conceptual speculation, but also as a functional and institutional one, in the language of policy frameworks and process charts? The process chart illustrated here is a framework to enmesh an artistic Mizan into the foundations of any project, programme or exhibition that would be developed in a contemporary art institution that acknowledges religion, belief and/or spirituality. It can be a process to understand the required methodologies of approach, signpost where resources may best be needed and most importantly, what expertise and insight is missing. Interrogating your project/programme/exhibition proposal through questions that represent the interconnected balance of the elements to create the conditions that allow belief to live, and art to thrive.

This speculative framework asks you to run your proposal first through Tradition. ‘What are the authorities of religion and belief identified?’ How can time be held to consider what approach to traditions in religion and belief the programme aims to take? Is it looking to the authorities of a belief system to be the guides to express it, the clergy or ulema, the priests and rabbis – or does it look to how individuals and communities manifest their belief as everyday practice? It will also interrogate how the proposed programme will engage with the communities that are connected to the religions, beliefs and/or spiritual practices that aim to be foregrounded, but also how the worldviews and paradigms of those who have a belief system that puts faith in divinities are part of shaping the programme.

Then to interrogate the proposal in identifying the boldness that is present for asking questions. Is there the ability to ask challenging questions from the framework of orthodox belief systems? Confidence in asking these questions can only come from the openness to receiving knowledge from traditional positions, and establishing trust with communities and individuals who hold them. This element also looks to identify the openness of questioning the orthodoxies and dominant cultures of the contemporary art ecosystems that can unconsciously or consciously encourage faith to be left at the door.

Alongside the elements of tradition and questioning, defining the motivations and boundaries for experimenting is next. What mechanisms in the proposal have the trust and investment pushing the artistic risk: the artists and creatives? The curators or educators? The clergy and congregations? Pushing artistic risk, but also holding reflection on what mechanisms are being acknowledged to create the boundaries of risk, which there will always be. This element will also acknowledge the openness for the work to develop and deliver in directions that may have not been considered at all – led by tradition, questioning and the holy spirit of artistic risk.

This speculation for a framework of Artistic Mizan, within an institutional language is being proposed for projects, programmes, and exhibitions that look to foreground religion, belief and spiritualities in the first instance. Yet, in the ideal, the framework can be used for any project or programme. The strive to open lost dialogues in the complexities of religion and belief in contemporary art doesn’t just happen if there is a collection or exhibition or artist that foregrounds them, but there is an ever-present texture. Just as belief is ever present in all our lives, as well as in the genesis of art history and art museums.